Galilean invariance

Galilean invariance or Galilean relativity is a principle of relativity which states that the fundamental laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames. Galileo Galilei first described this principle in 1632 in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems using the example of a ship travelling at constant velocity, without rocking, on a smooth sea; any observer doing experiments below the deck would not be able to tell whether the ship was moving or stationary. Today one can make the same comment about experiments in an aeroplane travelling at much greater velocity than a ship. The fact that the Earth orbits around the sun at approximately 30 km·s-1 offers a somewhat more dramatic example, though technically not an inertial reference frame.

Contents |

Formulation

Specifically, the term Galilean invariance today usually refers to this principle as applied to Newtonian mechanics, that is, Newton's laws hold in all inertial frames. In this context it is sometimes called Newtonian relativity.

Among the axioms from Newton's theory are:

- There exists an absolute space, in which Newton's laws are true. An inertial frame is a reference frame in relative uniform motion to absolute space.

- All inertial frames share a universal time.

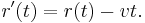

Galilean relativity can be shown as follows. Consider two inertial frames S and S' . A physical event in S will have position coordinates r = (x, y, z) and time t; similarly for S' . By the second axiom above, one can synchronize the clock in the two frames and assume t = t' . Suppose S' is in relative uniform motion to S with velocity v. Consider a point object whose position is given by r = r(t) in S. We see that

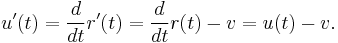

The velocity of the particle is given by the time derivative of the position:

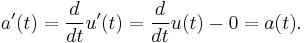

Another differentiation gives the acceleration in the two frames:

It is this simple but crucial result that implies Galilean relativity. Assuming that mass is invariant in all inertial frames, the above equation shows Newton's laws of mechanics, if valid in one frame, must hold for all frames. But it is assumed to hold in absolute space, therefore Galilean relativity holds.

Newton's theory versus special relativity

A comparison can be made between Newtonian relativity and special relativity.

Some of the assumptions and properties of Newton's theory are:

- The existence of infinitely many inertial frames. Each frame is of infinite size (covers the entire universe). Any two frames are in relative uniform motion. (The relativistic nature of mechanics derived above shows that the absolute space assumption is not necessary.)

- The inertial frames move in all possible relative uniform motion.

- There is a universal, or absolute, time.

- Two inertial frames are related by a Galilean transformation.

- In all inertial frames, Newton's laws, and gravity, hold.

In comparison, the corresponding statements from special relativity are same as the Newtonian assumption.

- Rather than allowing all relative uniform motion, the relative velocity between two inertial frames is bounded above by the speed of light.

- Instead of universal time, each inertial frame has its own time.

- The Galilean transformations are replaced by Lorentz transformations.

- In all inertial frames, all laws of physics are the same.

Notice both theories assume the existence of inertial frames. In practice, the size of the frames in which they remain valid differ greatly, depending on gravitational tidal forces.

In the appropriate context, a local Newtonian inertial frame, where Newton's theory remains a good model, extends to, roughly, 107 light years.

In special relativity, one considers Einstein's cabins, cabins that fall freely in a gravitational field. According to Einstein's thought experiment, a man in such a cabin experiences (to a good approximation) no gravity and therefore the cabin is an approximate inertial frame. However, one has to assume that the size of the cabin is sufficiently small so that the gravitational field is approximately parallel in its interior. This can greatly reduce the sizes of such approximate frames, in comparison to Newtonian frames. For example, an artificial satellite orbiting around earth can be viewed as a cabin. However, reasonably sensitive instruments would detect "microgravity" in such a situation because the "lines of force" of the Earth's gravitational field converge.

In general, the convergence of gravitational fields in the universe dictates the scale at which one might consider such (local) inertial frames. For example, a spaceship falling into a black hole or neutron star would (at a certain distance) be subjected to tidal forces so strong that it would be crushed. In comparison, however, such forces might only be uncomfortable for the astronauts inside (compressing their joints, making it difficult to extend their limbs in any direction perpendicular to the gravity field of the star). Reducing the scale further, the forces at that distance might have almost no effects at all on a mouse. This illustrates the idea that all freely falling frames are locally inertial (acceleration and gravity-free) if the scale is chosen correctly.[1]

Electromagnetism

Maxwell's equations governing electromagnetism possess a different symmetry, Lorentz invariance, under which lengths and times are affected by a change in velocity, which is then described mathematically by a Lorentz transformation.

Albert Einstein's central insight in formulating special relativity was that, for full consistency with electromagnetism, mechanics must also be revised such that Lorentz invariance replaces Galilean invariance. At the low relative velocities characteristic of everyday life, Lorentz invariance and Galilean invariance are nearly the same, but for relative velocities close to that of light they are very different.

Work, kinetic energy, momentum

Because the distance covered while applying a force to an object depends on the inertial frame of reference, so does the work done. Due to Newton's law of reciprocal actions there is a reaction force; it does work depending on the inertial frame of reference in an opposite way. The total work done is independent of the inertial frame of reference.

Correspondingly the kinetic energy of an object, and even the change in this energy due to a change in velocity, depends on the inertial frame of reference. The total kinetic energy of an isolated system also depends on the inertial frame of reference: it is the sum of the total kinetic energy in a center of momentum frame and the kinetic energy the total mass would have if it were concentrated in the center of mass. Due to the conservation of momentum the latter does not change with time, so changes with time of the total kinetic energy do not depend on the inertial frame of reference.

By contrast, while the momentum of an object also depends on the inertial frame of reference, its change due to a change in velocity does not.

See also

Notes

- ^ Taylor and Wheeler's Exploring Black Holes - Introduction to General Relativity, Chapter 2, p. 2-6.